The following is Part VIII of a multi-part series on value, segmentation and pricing by guest contributor Steven Forth, Partner at Rocket Builders and eFund Member. Read Part I here,Part II here, Part III here, Part IV here, Part V here, Part VI here, and Part VII here. Steven was recently called out as one of the top experts in B2B software pricing by OpenView Labs in Boston.

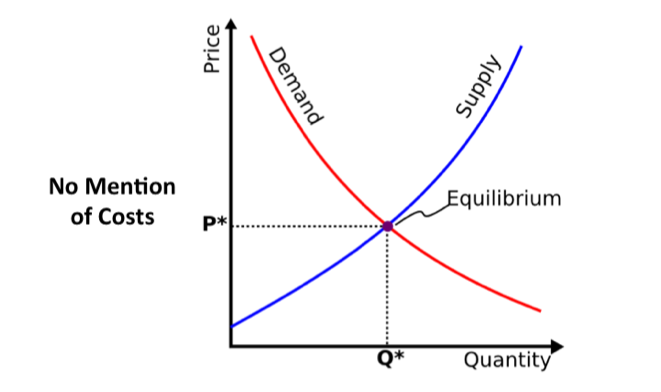

Whenever one talks about price someone is sure to ask about costs. People in business know that if you can’t cover your costs you can’t stay in business and that you cover your costs by setting the right price.

We even joke about this. “I lose money on every sale but I hope to make it up on volume.”

So what is wrong with basing one’s price on one’s costs? Well, two things.

If you are selling some sort of differentiated product or services, you optimize prices by understanding the value you create for your customer and claiming your fair share (see You can’t price software without focus and What is Value Anyway? (Why Creating Customer Value is at the Heart of Building a Business).

And if you are in a commodity market, the balance of supply and demand sets price, as the current situation in the oil industry reminds us.

Your customer does not really care about your costs. High costs do not justify a high price if you don’t create value. And if what you have to sell is valuable people will pay regardless of how low your costs are.

So what role do costs play in pricing? There is one case where cost-based pricing makes sense. When the value to the customer is uncertain or only the customer knows what the value is. This is especially true when the requirements (and deliverables) are unclear or will change over the course of a project. This is why many military and government contracts are cost plus. The value provided is not clear to the supplier (hopefully it is clear to the buyer). And why professionals who are unable to provide a differentiated service and where there is uncertainty about the scope of the work generally charge by the hour.

But companies in the innovation economy are generally not trying to create an undifferentiated services offer. Most of us aspire to create something with unique value, and find some niche where we can capture that value by charging a reasonable price. In this case, where do costs come to play?

Costs are one factor to consider when choosing market segments.

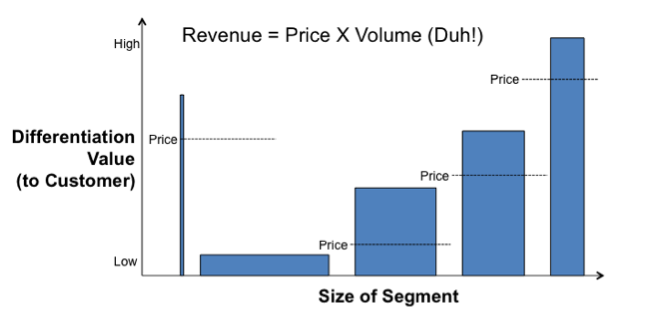

For example, let’s say a company is considering five different segments. One approach would be to test each segment and see what works, experimenting with different price levels and go-to-market strategies. Doing this in parallel (going after all of the segments at once) would be wasteful and a price that works for a high-value segment (a segment where the company provides a lot of value to the customer) won’t necessarily work for a lower value segment. Most companies would cycle through the different segments one after another, until they found one that works.

The problem with this approach is that a company might find a segment that works, sort of, but that is a long-way from the optimal segment. I have seen many companies get stuck in these sub-optimal segments and spin their wheels. Meanwhile, investors think “Hmm, there is a small market for this, but not very profitable, I think I’ll pass.” All the while, there is a more attractive segment that the company never gets to.

A better approach is to estimate the size of the segment, how much value you provide (the best way to do this with Economic Value Estimation see this series of posts on the LeveragePoint blog) and what price you think you can capture.

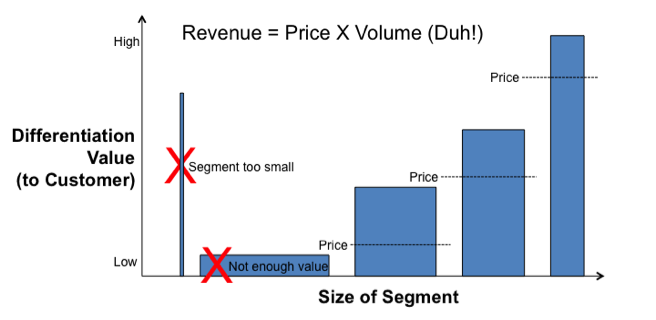

Once you have figured this out, and it can be at a very high level as long as what you are doing is directionally correct, you can start eliminating market segments. Here the first segment has been dropped as it is too small (the market opportunity is not big enough) and the second segment has been disqualified as not enough value is being created for customers relative to their alternatives.

Now consider costs. Estimate your customer acquisition costs for each of the remaining segments and then add in the cost to serve customers in that segment (how much will it cost to implement solutions for these customers, how much unpaid support will there be, do they require the development of unique features that no other segment needs).

Here the middle segment is one of those where one loses more and more money the more one sells.

How to choose between the remaining two segments? The segment on the left, which is larger in absolute terms, might work if you are in a market where there is a real first mover advantage and economies of scale. Here you would enter the segment with a penetration pricing strategy (you would set relatively low prices) and go for scale. You will probably need a lot of investment to make this work. In most cases the segment on the right is more attractive. It is smaller (a good thing as it is generally easier for a small company to enter a small segment) and the differentiation value is higher so a skimming pricing strategy (charging as high a price as possible) is more likely to work. The smaller market with a higher price point (and higher profitability) is often a good place to start.

Have a pricing question that you are willing to have discussed in a blog post? E-mail me at sforth@rocketbuilders.com and let’s discuss.

Steven Forth is a Vancouver consultant, investor and serial entrepreneur. He is a partner at Rocket Builders where his work is focused on market strategy including market segmentation, pricing and the design of revenue generation systems. He invests througheFund where he occasionally leads due diligence teams. His newest venture is TeamFit, a VentureLabs start-up building a platform for team building and collaboration.

Steven Forth is a Vancouver consultant, investor and serial entrepreneur. He is a partner at Rocket Builders where his work is focused on market strategy including market segmentation, pricing and the design of revenue generation systems. He invests througheFund where he occasionally leads due diligence teams. His newest venture is TeamFit, a VentureLabs start-up building a platform for team building and collaboration.